Integration of EasyBuild in LUMI¶

General information¶

LUMI, installed in a CSC data centre (Finland)), is one of the three planned EuroHPC pre-exascale systems meant to be installed in 2022-2023, together with Leonardo (installed at Cineca) and MareNostrum5 (installed at BSC). LUMI, which stands for Large Unified Modern Infrastructure, is hosted by the LUMI consortium, a consortium of 10 countries: Finland, Belgium, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Iceland, Norway, Poland, Sweden, and Switzerland. It was supposed to be installed by the end of 2021, but the global shortage of components and some technical problems have delayed the installation. The final hardware should be installed before mid 2022.

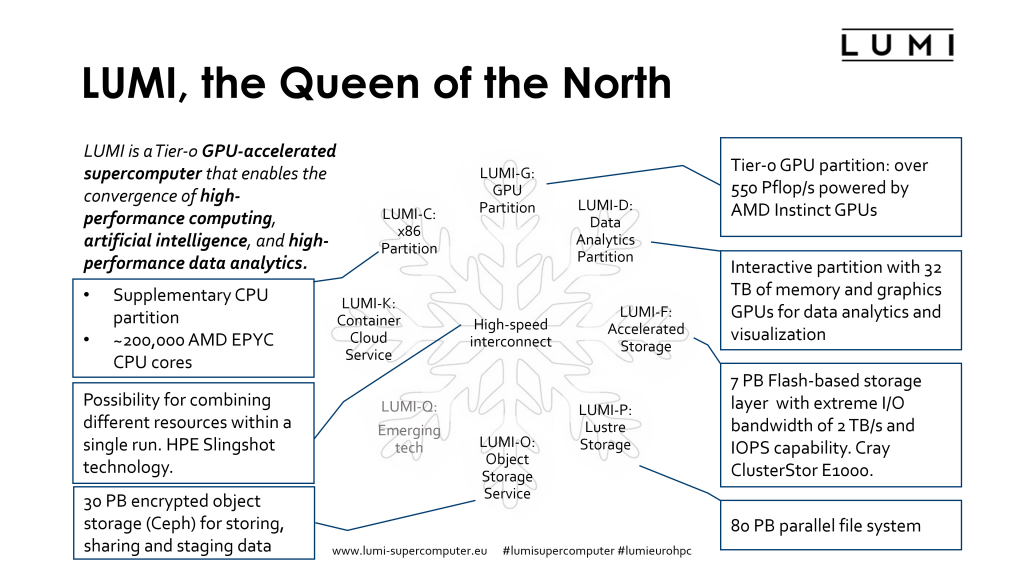

LUMI is an HPE Cray EX supercomputer with several partitions targeted for different use cases. It is also possible to run heterogeneous jobs across multiple partitions.

-

The main compute power is provided by the LUMI-G GPU compute partition consisting of 2,560 nodes. The LUMI-G node is a revolutionary compute node in the x86+GPU-world. It is also truly a "GPU first" system.

Each GPU compute node has a single 64 core AMD EPYC 7A53 "Trento" CPU and 4 MI250X GPUs. Each MI250X package contains two GPU compute dies connected to each other via AMD's InfinityFabric interconnect and 8 HBM2e memory stacks, 4 per die. The GPUs and CPU are all connected through AMD's InfinityFabric interconnect, creating a cache coherent unified memory space in each node. The Trento CPU is a Zen3 generation product but with an optimised I/O die that can run the InfinityFabric interconnect at a higher speed than standard Milan CPUs.

Each node also has 4 200Gbit/s SlingShot 11 interconnect cards, each connected directly to a different GPU package. Each node has 512GB HBM2e RAM spread evenly across the GPU dies and 512 GB of regular DDR4 DRAM connected to the CPU. The nodes are diskless nodes. The (very) theoretical peak performance of a GPU node is around 200 Tflops for FP64 vector operations or 400 TFlops for FP64 matrix operations.

-

The main CPU partition, called LUMI-C, consists of 1,536 nodes with two 64-core AMD EPYC 7,763 CPUs. Most nodes have 256 GB of RAM memory, but there are 128 nodes with 512 GB of RAM and 32 nodes with 1 TB of RAM. In the final system, each node will be equipped with one 200 Gbit/s SlingShot 11 interconnect card. These nodes are diskless nodes.

-

A section mostly meant for interactive data analysis consists of 8 nodes with two 64-core AMD EPYC 7742 CPUs and 4 TB of RAM per node. These nodes are connected to the interconnect through two 100 Gbit/s SlingShot 10 links.

-

The second part of LUMI-D, the data visualisation section, consists of 8 nodes with two 64-core AMD EPYC 7742 CPUs and 8 NVIDIA A40 GPUs each. Each node has 2 TB of RAM and is connected to the interconnect through two 100 Gbit/s SlingShot 10 links.

-

LUMI-K will be an OpenShift/Kubernetes container cloud platform for running microservices with roughly 50 nodes.

-

LUMI also has an extensive storage system

- There is a 7 PB flash-based storage system with 2 TB/s of bandwidth and high IOPS capability using the Lustre parallel file system and Cray ClusterStor E1000 technology.

- The main disk based storage contains of four 20 PB storage systems based on regular hard disks and also using the Lustre parallel file system.

- A 30 PB Ceph-based encrypted object storage system for storing, sharing and staging data will become available at a later date.

Challenges¶

-

LUMI comes with the HPE Cray Programming Environment (PE) with the Cray Compiling Environment (a fully Clang/LLVM-based C/C++ compiler and a Fortran compiler using a Cray frontend but LLVM-based backend) and GNU and AMD compilers repackaged by Cray. The HPE Cray PE uses an MPICH-based MPI implementation (with libfabric backend on SlingShot 11) and also comes with its own optimised mathematics libraries containing all the usual suspects you expect from an EasyBuild toolchain. The HPE Cray PE environment is managed outside EasyBuild, but EasyBuild has a mechanism to integrate with it.

Due to the specific hardware and software setup of LUMI using the EasyBuild common toolchains is anything but straightforward. Getting Open MPI, a key component of the foss toolchain, to work is a bit of a challenge at the moment. The Intel compilers are not a very good match with AMD CPUs. One needs to be very careful when choosing the target architecture for code optimisation (

-xHostwill not generate AVX/AVX2 code), most recent versions of MKL have performance problems and sometimes produce wrong results and some recent MPI versions also cause problems with AMD CPUs. -

LUMI has only a small central support team of 9 FTE. It is obvious that we cannot give the same level of support for software installations as some of the big sites such as JSC can do. Moreover, due to the nature of the LUMI environment with its Cray PE and novel AMD GPUs, installing software is more challenging than on your typical Intel + NVIDIA GPU cluster with NVIDIA/Mellanox interconnect. Given that the technology is very new, one can also expect a rapid evolution of the programming environment with a risk of breaking compatibility with earlier versions, and a need for frequent software updates in the initial years of operation to work around bugs or make new and important features available. So the maintenance cost of a the user application stack is certainly higher than on clusters based on more conventional technology. Early experience has also shown that we need to be prepared for potentially breaking changes on very short notice.

It also means that we have to be very agile when it comes to maintaining the software stack and that it is also impossible to thoroughly test all installations, so we must be able to make corrections quickly. This goes against a big central software stack, as in a central software stack it is nearly impossible to replace an installation that fails for some users outside maintenance intervals.

-

The central support team may be small (the above 9 FTE), but the LUMI consortium agreement states that the consortium countries also have to assist in providing support. Given that neither the LUMI User Support Team members nor the local support teams are employees of CSC this also means that much of the application support has to be delivered with very little rights on the system (at most a working directory that is readable for all users and writable for support people). So we need a setup where it is possible to help users installing applications while having only regular user rights on the system.

-

Due to the exploitation model and the small size of the central support team, license management is a pain. Users come to LUMI through 11 different channels (some with subchannels). Moreover it is the responsibility of the PI to invite users to a project and to ensure that they are eligible for LUMI use (taking into account, e.g., the European and USA export restrictions). At the central level we have no means to check who can use which software license. Hence we need a solution to distribute that responsibility also.

-

LUMI software support is based on the idea that users really want a customised software stack. They may say they want a central stack but only as long as it contains the software they need and not much more as they also do not want to search through long lists of modules. Nobody is waiting for 20 different configurations of a package, but the reality is that different users will want different versions with sometimes conflicting configurations, or compiled with different compilers.

We also note that some communities forego centrally installed software which may have better optimised binaries to build their own custom setup using tools such as Conda.

And even though modules go a long way in managing dependencies and helping to avoid conflicts, we expect that with the explosion of software used on HPC machines and the poor maintenance of that software, it will become increasingly difficult to find versions of dependencies that work for a range of programs, leading to cases where we may simply need to install a software package with different sets of dependencies simply because users want to use it together with other packages that have restrictions on the versions of those dependencies. Experienced Python users without doubt know what a mess this can create and how even a single user sometimes needs different virtual environments with different installations to do their work.

Solution with EasyBuild and Lmod¶

On LUMI we selected EasyBuild as our primary software installation tool, but also offer some limited support for Spack. EasyBuild was selected as there is already a lot of experience with EasyBuild in several of the LUMI consortium countries, and as it is a good fit with the goals of the EuroHPC JU as they want to establish a European HPC ecosystem with a European technology option at every level. The developers of EasyBuild are also very accessible and it helps that the lead developer and several of the maintainers are from LUMI consortium countries.

We use Lmod as the module tool. We basically had the choice between Lmod and the old C implementation of TCL Environment Modules as HPE Cray does not support the more modern Environment Modules 4 or 5 developed in France. Support for Lmod is excellent in EasyBuild and Spack, and Lua is also a more modern language to work with than TCL.

Software stacks¶

On LUMI we offer users the choice between multiple software stacks, offered through hand-written Lmod modules.

-

The CrayEnv stack is really just a small layer on top of the HPE Cray PE in which we provide a few additional tools and help the user with managing the environment for the HPE Cray PE.

The HPE Cray PE works with a universal compiler wrapper that sets some optimisation options for the supported compilers and sets the flags to compile and link with the MPI, optimised scientific libraries and some other libraries provided with the PE. It does so based on which modules are loaded. The CPU and GPU targets and the MPI fabric library are selected through so-called target modules, typically loaded during shell initialisation, while compiler, MPI and scientific libraries are typically loaded through the so-called

PrgEnv-*modules (one for each supported compiler). The CrayEnv software stack module will take care of ensuring that a proper set of target modules is loaded depending on the node type on which the module is loaded, and also ensure that the proper set of target modules is reloaded after amodule purge.The environment is also enriched with a number of build tools that are not installed in the OS image or only in an older version. These tools are often build with EasyBuild with the

SYSTEMtoolchain though we do not make EasyBuild itself available to users in that stack. -

The LUMI stack is a software stack which is mostly managed with EasyBuild. The stack is versioned based on the version of the HPE Cray PE which makes it easy to retire a whole stack when the compilers are retired from the system. If we need the same software in two different stacks, it is simply compiled twice, even if it is only installed with the system compilers, to make retiring software easier without having to track dependencies (we now simply have to remove a few directories to remove a whole software stack which will not have an impact on the other stacks). The exception are a few packages installed from binaries that are installed in a separate area and available across all software stacks (e.g., ARM Forge and Vampir). The LUMI stack provides optimised binaries for each node type of LUMI, but some software that is not performance-critical is compiled only once. To this end we have a partition corresponding to each node type, but also a common partition which is included with the software of all other partitions. Software in that common partition can only have dependencies in the common partition though.

For now we keep the central LUMI software stack very small, but we provide an easy and fully transparent mechanism for the user to install software in their project directory that integrates fully with the LUMI stack. The user only needs to set an environment variable pointing to the project space.

In the future we envision that more software stacks may become available on LUMI as at least one local support organisation wants to build their own stack. We also hope to find a solution to get the foss toolchain working on at least the CPU nodes of LUMI with minimal changes in a future collaboration with HPE.

EasyBuild for software management¶

The second component to our solution is EasyBuild. EasyBuild can give a very precise description of

all the steps needed to build a package while the user needs to give very few arguments to the eb command

to actually do the installation. It is also robust enough that with a proper module to configure EasyBuild,

an installation done by one user on LUMI will reproduce easily in the environment of another user.

The fact that each easyconfig file contains a very precise list of dependencies, including versions and

not only the names of the dependencies, is both a curse and a blessing. It is a curse when we need to upgrade

to a new compiler and also want to upgrade versions of certain dependencies, as a lot of easyconfig files need

to be checked and edited. In those cases the automatic concretiser of Spack may help to get running quicker.

However, that very precise description is also a blessing when communicating with users as you can communicate with them through EasyBuild recipes (and possibly an easystack file, which defines a list of easyconfig files to install) rather than having a part of the specification in command line options of the tool. So a user doesn't need to copy long command lines and as a support person you know exactly what EasyBuild will do, so this leaves less room for errors and difficult to solve support tickets. (Though note that with Spack environments you can also give a full specification in an Environment manifest.)

Offering EasyBuild in the LUMI stacks¶

The LUMI software stack is implemented as an Lmod hierarchy with two levels. On top of it EasyBuild is used with a flat naming scheme (though we did consider a hierarchical one as well).

The modules that load a specific version of the software stack are hand-written in Lua. The first level

(a module called LUMI) is the version of the software stack,

the second level (a module called partition) then choses the particular set of hardware to

optimise for. The LUMI module will autoload the most suited partition module for the hardware,

but users can overwrite this choice, e.g., for cross-compiling which is a common practice on

HPE Cray systems but not without difficulties and hence not always possible.

The LUMI and partition module combo also check a default location for the user software stack, and

an environment variable that is used to point to a different location for the user software stack.

If a user software stack is found, its modules are automatically added to the stack. There are also

some partition modules that do not correspond to particular hardware but are only used during software

installation, to install software in "special" locations. E.g., the module partition/common is used to

install some software for all partitions without binaries optimised specifically for each partition.

On LUMI, a selection of build and version control tools is currently installed that way.

The LUMI and partition modules are both implemented in a generic way. Instances in the module tree are

symbolic links to the generic implementations, and so-called Lmod introspection functions are used by

the modules to determine their function from the location in the module tree. This makes it easy to correct

bugs and extend the module files without having to go over different implementations in different locations.

To enable all this functionality, including the common partition, a double module structure was needed

to ensure the proper working of the Lmod hierarchy. The infrastructure tree is implemented following

all proper rules for an Lmod hierarchy. It houses the LUMI and partition modules among others, but

also the toolchain modules so that they can be configured specifically for each version of the LUMI

software stack and partition. The software module tree contains all software installed through

EasyBuild, with room to expand to manually installed software or software installed with Spack

should this turn out to be necessary and safe to combine with EasyBuild-managed software.

EasyBuild is configured through some configuration modules that set a range of EASYBUILD_* variables

to configure EasyBuild. There is again only a single EasyBuild configuration module implemented in Lua,

but it appears with three different names in multiple locations in the infrastructure module tree,

and again Lmod introspection functions are used by the module to determine its specific function.

There are three configurations for EasyBuild: One for installation in the infrastructure module tree,

one for installation in the main software tree and one for installation in the user software tree.

By using just a single implementation for all three functions, we ensure that the different configurations

remains consistent. This is important, e.g., to guarantee that the user configuration builds correctly

upon the centrally installed stack, so any change to the structure of the latter should also propagate

to the configuration of the former.

EasyBuild on LUMI¶

Custom toolchains¶

The LUMI EasyBuild solution is not based on the common toolchains as the HPE Cray Programming Environment is the primary development environment on LUMI for which we also obtain support from HPE and as the common toolchains both post problems on LUMI. So far we have not yet succeeded to ensure proper operation of Open MPI on LUMI which is a showstopper for working with the FOSS toolchain hierarchy. There is also no support yet for AMD GPUs in the common toolchains. Moreover, the FOSS toolchain is becoming a very powerful vehicle by the inclusion of FlexiBLAS and now also efforts to build an Open MPI configuration that supports both CPU nodes and NVIDIA GPU nodes but the downside of this is that it has also become a very complicated setup to adapt if you need something else, as we do on LUMI. The Intel toolchain also has its problems. Intel does not support oneAPI on AMD processors. Though Intel MPI can in principle run on SlingShot as it is also based on libfabric and will be used on Aurora, a USA exascale system build by Intel with HPE Cray as a subcontractor for the hardware, users of AMD systems have reported problems with recent versions. MKL does not only have performance problems, but several sources also report correctness problem, especially in computational chemistry DFT codes.

Instead we employ toolchains specific for the three (soon four) versions of the HPE Cray Programming

Environment: HPE Cray's own Cray Compiler Environment compilers with a C/C++ compiler based on Clang/LLVM

with some vendor-specific plugins and a Fortran compiler that compiles HPE Cray's frontend with a backend

based on LLVM, the GNU Compiler Collection with its C/C++ and Fortran compiler, the AMD Optimizing

C/C++ and Fortran Compilers (AOCC) and soon also a version employing the AMD ROCm compilers for the

AMD GPU compute nodes. The toolchains used on LUMI are a further evolution of the toolchains used

at CSCS with many bug corrections in the AOCC-based toolchain and better support for toolchain options

specified through toolchainopts. They should however be largely compatible with the EasyConfigs

in the CSCS repository.

The toolchains are loaded through modules, generated with EasyBuild and a custom EasyBlock, that replace

the top PrgEnv modules from the HPE Cray Programming Environment. These modules then use the modules provided

by HPE Cray to load the actual compilers, compiler wrappers, MPI libraries and scientific libraries, and

the target modules that determine how the main modules work. So contrary to many other EasyBuild toolchains,

the compilers, MPI and scientific libraries are not installed through EasyBuild.

External modules¶

EasyBuild supports the use of modules that were not installed via EasyBuild.

We refer to such modules as external modules.

External modules do not define the EBROOT* and EBVERSION* environment variables that are present

in EasyBuild-generated modules and that EasyBuild uses internally in some easyblocks and easyconfigs,

and they also have no corresponding easyconfig file that can tell EasyBuild about further dependencies.

External modules are used extensively on Cray systems to interface with the Cray PE (which comes with its own

modules and cannot be installed via EasyBuild):

external modules can be used as dependencies,

by including the module name in the dependencies list,

along with the EXTERNAL_MODULE constant marker.

As an example, the Cray PE contains its own FFTW module, called cray-fftw.

To use this module as a dependency, you should write the following in your easyconfig file:

dependencies = [('cray-fftw', EXTERNAL_MODULE)]

For such dependencies, EasyBuild will:

-

load the module before initiating the software build and install procedure

-

include a

module loadstatement in the generated module file (for runtime dependencies) -

but it will not go looking for a matching easyconfig file.

Note

The default version of the external module will be loaded unless a specific version is given as dependency, and here that version needs to be given as part of the name of the module and not as the second element in the tuple.

dependencies = [('cray-fftw/3.3.8.12', EXTERNAL_MODULE)]

If the specified module is not available, EasyBuild will exit with an error message stating that the dependency can not be resolved because the module could not be found, without searching for a matching easyconfig file from which it could generate the module.

The metadata

for external modules can be supplied through one or more metadata files, pointed to by the --external-modules-metadata

configuration option (or corresponding environment variable).

These files are expected to be in INI format, with a section per module name

and key-value assignments specific to that module.

The following keys are supported by EasyBuild:

- name: software name(s) provided by the module

- version: software version(s) provided by the module

- prefix: installation prefix of the software provided by the module

For instance, the external module version loaded by the dependency cray-fftw can be specified as follows:

[cray-fftw]

name = FFTW

prefix = FFTW_DIR/..

version = 3.3.8.10

This will then ensure that EasyBuild knows the equivalent EasyBuild name(s), version(s) and root of the

software installation for use in easyblocks. It will also create the corresponding $EBROOT* and

$EBVERSION* environment variables in the build environment after loading the external module

so that the module resembles more a regular EasyBuild-generated module and so that these environment

variables can be used, e.g., in options to configure or cmake.

EasyBuild also includes a default metadata file that will be used, but that one can be very much out-of-date. And if no information for a particular module is present in the metadata files, EasyBuild will even try to extract the information out of certain environment variables that are used by several Cray PE modules.

On LUMI, users in generally don't need to be too concerned about the metadata file as the EasyBuild-user and other

EasyBuild configuration modules take care of pointing to the right metadata file, which is specific for each version of the

Cray PE and hence each version of the LUMI software stack.

Software-specific easyblocks¶

EasyBuild comes with a lot of software-specific easyblocks.

These have only been tested with the common toolchains

in the automated EasyBuild test procedures. As a result, many of those easyblocks will fail with the Cray toolchains

(and with many other custom toolchains). A common problem is that they don't recongnise the compilers as they test

for the presence of certain modules and hence simply stop with an error message that the compiler is not

recognised, but there may also be more subtle problems, like explicitly checking for the name of a dependency rather

than for the presence of the corresponding EBROOT and EBVERSION environment variables through the EasyBuild API.

Hence it may fail to recognise external modules that have a different name than the name that EasyBuild uses for

the package.

For this reason we (and CSCS) tend to use the generic easyblocks more often, specifying configuration and build options by hand in the corresponding easyconfig parameters rather than relying on the logic in an easyblock to set the parameter for us based on the dependencies that are present. In some cases, the easyblocks are adapted, but this poses a maintenance problem. Contributing the modified easyblock back to the EasyBuild community is no guarantee that it remains compatible as the Cray-specific code cannot currently be tested in the automated test procedures due to lack of access to the Cray PE and lack of suitable easyconfig files to do the tests. However, keeping the code in our own repositories is no full solution either as the easyblock may need maintenance when a new version of EasyBuild with an updated easyblock appears.

Other LUMI-specific EasyBuild settings¶

On LUMI, we do use a slightly customised version of the flat naming scheme but that is mostly because we are not interested in the categorisation of modules in module classes as this categorisation is too arbitrary. There are simply too many modules that could be put in multiple classes, something which is currently not supported. We decided to remove that level altogether from the module directory tree.

Further reading and information¶

- LUMI web site

- LUMI user documentation web site

- So far most LUMI trainings were done by HPE Cray and their training materials cannot be distributed freely, but there is some additional training material from the LUMI User Support Team.

- This EasyBuild training web site also contains:

- LUMI GitHub repositories:

- LUMI-SoftwareStack is the repository that contains all our Lmod modules, custom easyblocks and the easyconfigs of software that has already made it into the central stack. Its structure is inspired on that of the CSCS repository. The repository also contains ample technical information on our implementation which can also be browsed through the lumi-supercomputer GitHub pages.

- LUMI-EasyBuild-contrib is our main repository

of easyconfig files for installation in the user space. Many of these may require more testing or support for

more configurations. Most subdirectories with easyconfig files also contain a

README.mdfile that explains the choices we made when implementing the easyconfig file.

- Other sites with Cray hardware that also use EasyBuild

next: The EasyBuild community - (back to overview page)